【The Economist】The long march abroad

2016年7月15日

IN FAR WESTERN China on the edge of the Gobi desert, 17-year-olds in a social-studies class are discussing revolution (the Russian one) and the use and abuse of nationalism (Germany, Italy). When the teacher asks what “totalitarianism” is, a girl immediately replies: “One leader, one ideology, no human rights.” These are Chinese pupils in a Chinese classroom studying the second world war, but by attending Lanzhou Oriental Canadian School they have already written themselves out of at least part of a Chinese future. They will all go to university abroad, many to Canada, others to the United States, Australia and Britain. So great is Chinese demand for foreign schooling that even here in Gansu, China’s second-poorest province, a new block is being built to house more students; the hoardings on the building site are plastered with posters about “The Chinese Dream”, a slogan Xi Jinping launched in 2012 to promote the country’s “great revival”. But like hundreds of thousands of people across China, these teenagers and their families harbour a different dream: escape.

The extraordinary outflow of people from China is one of the most striking trends of recent decades. Since the country started opening up in 1978, around 10m Chinese have moved abroad, according to Wang Huiyao of the Centre for China and Globalisation(CCG), a think-tank in Beijing. Only India and Russia have a larger diaspora, both built up over a much longer period. The mass exodus of students like those at Lanzhou Oriental is just one part of the story. Since 2001 well over 1m Chinese have become citizens of other countries, most often America; a far larger number have taken up permanent residence abroad, a status often tied to a specific job that may last for years and can turn into citizenship.

Chinese make up the bulk of individuals who are given investor visas, a fast-track immigration system offered by many countries to the super-wealthy. Others are just moving their money offshore, investing in foreign companies or buying property. Officially Chinese citizens are limited to moving $50,000 abroad a year, but many are finding inventive ways to get round that rule, including overpaying for imports, forging deals with foreign entities and even starting, then losing, fake lawsuits against foreign entities, triggering huge “damages”.

An export industry

Studying abroad has become an ambition for the masses: 57% of Chinese parents would send their child overseas to study if the family had the means, according to the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. Even Mr Xi sent his daughter to study at Harvard. Nor is this open only to the super-rich. Liang Yuqi from Zhangye, a city close to Lanzhou, is being quietly guided towards a relatively cheap Canadian state university to study psychology. Her parents are government officials who have never been abroad (cadres must hand in their passport) and will pool money from relatives to fund her foreign education. The sacrifice is worth it, says her mother: in middle school Yuqi was “fat” and “mediocre”, now she is confident and asks lots of questions. Many others are spending their all to make the break. More than half a million university students went overseas last year.

This aspirational market is served by hundreds of international schools in China. Some cater for non-Chinese citizens, often the foreign-born offspring of returning Chinese. Since 2003 a growing number of regular Chinese schools, such as Lanzhou Oriental Middle School, have launched lucrative international programmes for Chinese passport-holders (fees at Lanzhou Oriental’s international arm are 70,000 yuan ($11,000) a year, 11 times the price of a regular education there). Their popularity caused a backlash against the use of public facilities and funds to send kids to study abroad after they finished school. Beijing city government and a number of provincial authorities have stopped approving new international programmes, and the education ministry is pondering nationwide restrictions. But students are leaving younger and younger. Since 2005 the number of Chinese secondary-school pupils in America alone has increased almost 60-fold, to 35,000.

Of the 4m Chinese who have left to study abroad since 1978, half have not returned, according to the education ministry. By most unofficial counts the share is even larger. In some fields the brain drain is extreme: almost all of China’s best science students go abroad for their PhDs, and 85% of Chinese science and engineering graduates with American PhDs had not returned home five years after leaving, a study by the National Science Foundation found this year. Many of the teenagers at Lanzhou Oriental Canadian School know that they are responsible for their entire family’s future: 16-year-old Hai Yingqi says she has to get a good enough job upon graduation to allow her parents, young brother and all four grandparents to emigrate.

One, two, flee

China has long seen education as a passport to success, which helps explain why the middle class is now focusing on foreign schools and universities. One Beijing businesswoman preparing to give birth in America says she wants to avoid sending the child to a Chinese school because she would have to bribe her way into a good primary school, and then “make sure the teacher is happy”—more bribes: “It’s not the money I mind, but the trouble.” Another parent questions how a child can learn values in such a system, and cites the corrupting influence of “patriotic education”, the compulsory propaganda classes all pupils must attend, where there is only one right answer and nothing can be questioned.

Others find different exit strategies. The super-rich can, in essence, buy foreign residency. Chinese citizens who invest at least ?2m ($3m) in Britain are promised permanent residency in five years; Australia offers a similar scheme for A$5m ($3.6m). Around 70,000 Chinese millionaires have emigrated to Canada since 2008 under an immigrant investor scheme. This is no longer in operation, but the country is now encouraging Chinese entrepreneurs and startups. Hong Kong has cracked down on mainland mothers giving birth there to gain Hong Kong passports (and citizenship has become less appealing than it used to be), but birth tourism to America and other countries is increasing. And many of those working for multinational companies eventually transfer elsewhere.

Businesspeople who have returned to the mainland now lead some of China’s most innovative companies. But most come back only once they have secured an escape route for themselves or their children. The government has sponsored some expensive schemes to lure academics back to China, and some have taken up the invitation, having first made sure that their children were born abroad so they would be able to choose where to live in future. Yao Ming, a famous 2.29-metre-tall basketball player, is one of China’s icons, a true product of the Communist Party (which encouraged his exceptionally tall parents to marry), but his daughter, now six, was born in America. Chen Kaige, one of China’s best-known film directors, has at least two American children; Gong Li, a film star, and Jet Li, a Chinese martial-arts actor, both have Singaporean passports.

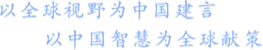

Outflows of capital, even more than people, directly mirror political risk. The torrent of cash flowing out of China almost exactly matches fears about the strength of the economy and the government’s capacity to handle it (see chart). In the second half of 2015, for example, capital moved abroad at an annual rate of $1 trillion in response to a fragile economy, the government’s botched attempt to intervene in the falling stockmarket and a slight but unexpected drop in the yuan. The government temporarily slowed that outflow by stepping up capital controls earlier this year and taking some sensible decisions on the economy. Yet as with so many problems, the party dealt with the immediate crisis, not the underlying cause.

China has long been a land of emigration, establishing small outposts of its people in almost every country in the world. Their main motive was to escape poverty. But those now bowing out are among China’s richest and most skilled. It is a profound indictment of their country that being able to leave it is such a strong sign of success.

From The Economist,2016-7-9